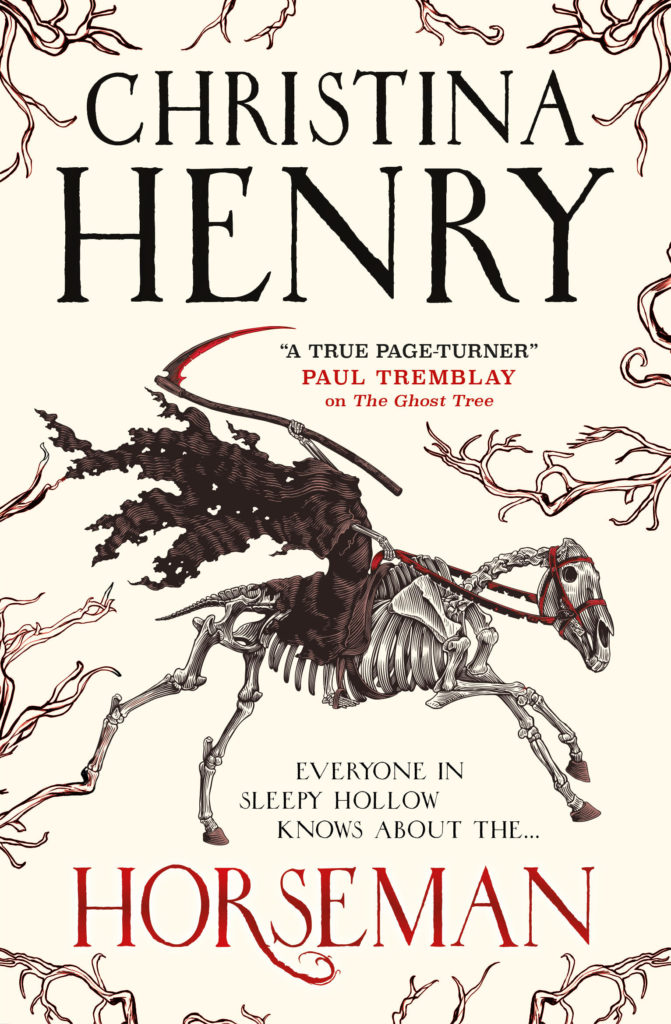

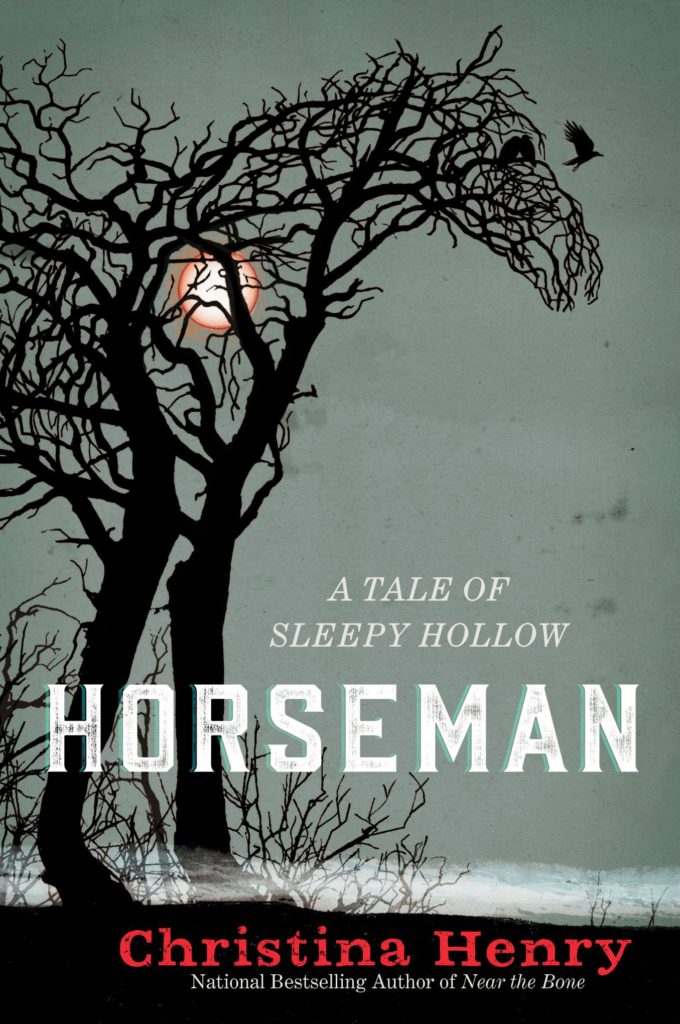

September has arrived, and that means that my latest book HORSEMAN: A TALE OF SLEEPY HOLLOW is nearly here! It will be out on September 28th, 2021, just in time for your spooky season reading. I’ve got a sneak peek at the first chapter for you below, followed by the U.S. and UK covers and preorder links galore. I hope you join me in Sleepy Hollow on September 28th!

CHAPTER ONE

Of course I knew about the Horseman, no matter how much Katrina tried to keep it from me. If ever anyone brought up the subject within my hearing, Katrina would shush that person immediately, her eyes slanting in my direction as if to say, “Don’t speak of it in front of the child.”

I found out everything I wanted to know about the Horseman anyway, because children always hear and see more than adults think they do. Besides, the story of the Headless Horseman was a favorite in Sleepy Hollow, one that had been told and retold almost since the village was established. It was practically nothing to ask Sander to tell me about it. I already knew the part about the Horseman looking for a head because he didn’t have one. Then Sander told me all about the schoolmaster who looked like a crane and how he tried to court Katrina and how one night the Horseman took the schoolmaster away, never to be seen again.

I always thought of my grandparents as Katrina and Brom though they were my grandmother and grandfather, because the legend of the Horseman and the crane and Katrina and Brom were part of the fabric of the Hollow, something woven into our hearts and minds. I never called them by their names, of course—Brom wouldn’t have minded, but Katrina would have been very annoyed had I referred to her as anything except “Oma.”

Whenever someone mentioned the Horseman, Brom would get a funny glint in his eye and sometimes chuckle to himself, and this made Katrina even more annoyed about the subject. I always had the feeling that Brom knew more about the Horseman than he was letting on. Later I discovered that, like so many things, this was both true and not true.

On the day that Cristoffel van den Berg was found in the woods without his head, Sander and I were playing Sleepy Hollow Boys by the creek. This was a game that we played often. It would have been better if there were a large group but no one ever wanted to play with us.

“All right, I’ll be Brom Bones chasing the pig and you be Markus Baas and climb that tree when the pig gets close,” I said, pointing to a maple with low branches that Sander could easily reach.

He was still shorter than me, a fact that never failed to irritate him. We were both fourteen and he thought that he should have started shooting up like some of the other boys in the Hollow.

“Why are you always Brom Bones?” Sander asked, scrunching up his face. “I’m always the one getting chased up a tree or having ale dumped on my head.”

“He’s my opa,” I said. “Why shouldn’t I play him?”

Sander kicked a rock off the bank and it tumbled into the stream, startling a small frog lurking just under the surface.

“It’s boring if I never get to be the hero,” Sander said.

I realized that he was always the one getting kicked around (because my opa could be a bit of a bully—I knew this even though I loved him more than anyone in the world—and our games were always about young Brom Bones and his gang). Since Sander was my only friend and I didn’t want to lose him, I decided to let him have his way—at least just this once. However, it was important that I maintain the upper hand (“a Van Brunt never bows his head for anyone,” as Brom always said), so I made a show of great reluctance.

“Well, I suppose,” I said. “But it’s a lot harder, you know. You have to run very fast and laugh at the same time and also pretend that you’re chasing a pig and you have to make the pig noises properly. And you have to laugh like my opa—that great big laugh that he has. Can you really do all that?”

Sander’s blue eyes lit up. “I can, I really can!”

“All right,” I said, making a great show of not believing him. “I’ll stand over here and you go a little ways in that direction and then come back, driving the pig.”

Sander obediently trotted in the direction of the village and turned around, puffing himself up so that he appeared larger.

Sander ran toward me, laughing as loud as he could. It was all right but he didn’t really sound like my opa. Nobody sounded like Brom, if truth be told. Brom’s laugh was a rumble of thunder that rolled closer and closer until it broke over you.

“Don’t forget to make the pig noises, too,” I said.

“Stop worrying about what I’m doing,” he said. “You’re supposed to be Markus Baas walking along without a clue, carrying all the meat for dinner in a basket for Arabella Visser.”

I turned my back on Sander and pretended to be carrying a basket, a simpering look on my face even though Sander couldn’t see my expression. Men courting women always looked like sheep to me, their dignity drifting away as they bowed and scraped. Markus Baas looked like a sheep anyway, with his broad blank face and no chin to speak of. Whenever he saw Brom he’d frown and try to look fierce. Brom always laughed at him, though, because Brom laughed at everything, and the idea of Markus Baas being fierce was too silly to contemplate.

Sander began to snort, but since his voice wasn’t too deep he didn’t really sound like a pig—more like a small dog whining in the parlor.

I turned around, ready to tell Sander off and demonstrate proper pig-snorting noises. That’s when I heard them.

Horses. Several of them, by the sound of it, and hurrying in our direction.

Sander obviously hadn’t heard them yet, for he was still galloping toward me, waving his arms before him and making his bad pig noises.

“Stop!” I said, holding my hands up.

He halted, looking dejected. “I wasn’t that bad, Ben.”

“That’s not it,” I said, indicating he should come closer. “Listen.”

“Horses,” he said. “Moving fast.”

“I wonder where they’re going in such a hurry,” I said. “Come on. Let’s get down onto the bank so they won’t see us from the trail.”

“Why?” Sander asked.

“So that they don’t see us, like I said.”

“But why don’t we want them to see us?”

“Because,” I said, impatiently waving at Sander to follow my lead. “If they see us they might tell us off for being in the woods. You know most of the villagers think the woods are haunted.”

“That’s stupid,” Sander said. “We’re out here all the time and we’ve never found anything haunted.”

“Exactly,” I said, though that wasn’t precisely true. I had heard something, once, and sometimes I felt someone watching us while we played. The watching someone never felt menacing, though.

“Though the Horseman lives in the forest, he doesn’t live anywhere near here,” Sander continued. “And of course there are witches and goblins, even though we’ve never seen them.”

“Yes, yes,” I said. “But not here, right? We’re perfectly safe here. So just get down on the bank unless you want our game ruined by some spoiling adult telling us off.”

I told Sander that we were hiding because we didn’t want to get in trouble, but really I wanted to know where the riders were going in such a hurry. I’d never find out if they caught sight of us. Adults had an annoying tendency to tell children to stay out of their business.

We hunkered into the place where the bank sloped down toward the stream. I had to keep my legs tucked up under me or else my shoes would end up in the water, and Katrina would twist my ear if I came home with wet socks.

The stream where we liked to play ran roughly along the same path as the main track through the woods. The track was mostly used by hunters, and even on horseback they never went past a certain point where the trees got very thick. Beyond that place was the home of the witches and the goblins and the Horseman, so no one dared go farther. I knew that wherever the riders were headed couldn’t be much beyond a mile past where Sander and I peeked over the top of the bank.

A few moments after we slipped into place, the group of horses galloped past. There were about half a dozen men—among them, to my great surprise, Brom. Brom had so many duties around the farm that he generally left the daily business of the village to other men. Whatever was happening must be serious to take him away during harvest time.

Not one of them glanced left or right, so they didn’t notice the tops of our heads. They didn’t seem to notice anything. They all appeared grim, especially my opa, who never looked grim for anything.

“Let’s go,” I said, scrambling up over the top of the bank. I noticed then that there was mud all down the front of my jacket. Katrina would twist my ear for sure. “If we run we can catch up to them.”

“What for?” Sander asked. Sander was a little heavier than me and he didn’t like to run if he could help it.

“Didn’t you see them?” I said. “Something’s happened. That’s not a hunting party.”

“So?” Sander said, looking up at the sky. “It’s nearly dinnertime. We should go back.”

I could tell that now that his chance to play Brom Bones had been ruined, he was thinking about his midday meal and didn’t give a fig for what might be happening in the woods. I, on the other hand, was deeply curious about what might set a party of men off in such a hurry. It wasn’t as if exciting things happened in the Hollow every day. Most days the town was just as sleepy as its name. Despite this—or perhaps because of it—I was always curious about everything, and Katrina often reminded me that it wasn’t a virtue.

“Let’s just follow for a bit,” I said. “If they go too far we can turn back.”

Sander sighed. He really didn’t want to go, but I was his only friend the same as he was mine.

“Fine,” he said. “I’ll go a short way with you. But I’m getting hungry, and if nothing interesting happens soon I’m going home.”

“Very well,” I said, knowing that he wouldn’t go home until I did, and I didn’t plan on turning around until I’d discovered what the party of horsemen was chasing.

We stayed close to the stream, keeping our ears pricked for the sounds of men or horses. Whatever the adults were about, they surely wouldn’t want children nearby—it was always that way whenever anything interesting occurred—and so we’d have to keep our presence a secret.

“If you hear anyone approaching, just hide behind a tree,” I said.

“I know,” Sander said. He had mud all down the front of his jacket, too, and he hadn’t noticed it yet. His mother would tell him off over it for hours. Her temper was the stuff of legends in the Hollow.

We had only walked for about fifteen minutes when we heard the horses. They were snorting and whinnying low, and their hooves clopped on the ground like they were pawing and trying to get away from their masters.

“The horses are upset,” I whispered to Sander. We couldn’t see anything yet. I wondered what had bothered the animals so much.

“Shh,” Sander said. “They’ll hear us.”

“They won’t hear us over that noise,” I said.

“I thought you wanted to sneak up on them so they wouldn’t send us away?” he said.

I pressed my lips together and didn’t respond, which was what I always did when Sander was right about something.

The trees were huddled close together, chestnut and sugar maple and ash, their leaves just starting to curl at the edges and shift from their summer green to their autumn colors. The sky was covered in a patchwork of clouds shifting over the sun, casting strange shadows. Sander and I crept side by side, our shoulders touching, staying close to the tree trunks so we could hide behind them if we saw anyone ahead. Our steps were silent from long practice at sneaking about where we were not supposed to be.

I heard the murmur of men’s voices before I saw them, followed immediately by a smell that was something like a butchered deer, only worse. I covered my mouth and nose with my hand, breathing in the scent of earth instead of whatever half-rotten thing the men had discovered. My palms were covered in drying mud from the riverbank.

The men were standing on the track in a half circle, their backs to us. Brom was taller than any of them, and even though he was the oldest, his shoulders were the broadest, too. He still wore his hair in a queue like he had when he was young, and the only way to tell he wasn’t a young man were the streaks of gray in the black. I couldn’t make out the other five men with their faces turned away from us—they all wore green or brown wool coats and breeches and high leather boots, the same style as twenty years before. There were miniatures and sketches of Katrina and Brom in the house from when they were younger, and while their faces had changed, their fashions had not. Many things never changed in the Hollow, and clothing was one of them.

“I want to see what they’re looking at, ” I whispered close to Sander’s ear and he batted at me like I was an annoying fly.

His nose was crumpled and he looked a little green. “I don’t. It smells terrible.”

“Fine,” I said, annoyed. Sander was my only friend but sometimes he lacked a sense of adventure. “You stay here.”

“Wait,” he said in low whisper as I crept ahead of him. “Don’t go so close.”

I turned back and flapped my hand at him, indicating he should stay. Then I pointed up at one of the maples nearby. It was a big one, with a broad base and long branches that protruded almost over the track. I hooked my legs around the trunk and shimmied up until I could grab a nearby branch, then quickly climbed until I could see the tops of the men’s heads through the leaves. I still couldn’t quite see what they were looking at, though, so I draped over one of the branches and scooted along until I had a better look.

As soon as I saw it, I wished I’d stayed on the ground with Sander.

Just beyond the circle of men was a boy—or rather, what was left of a boy. He lay on his side, like a rag doll that’s been tossed in a corner by a careless child, one leg half-folded. A deep sadness welled up in me at the sight of him lying there, forgotten rubbish instead of a boy.

Something about this sight sent a shadow flitting through the back of my mind, the ghost of a thought, almost a memory. Then it disappeared before I could catch it.

He was dressed in simple homespun pants and shirt, a brown wool jacket much like my own over it. On his feet were leather moccasins, and that was how I knew it was Cristoffel van den Berg, because his family was too poor to afford shoe leather and cobbled soles, and all of the Van den Bergs wore soft hide shoes like the Lenape people. If it weren’t for the moccasins I wouldn’t have known him at all, because his head was missing. So were his hands.

Both the head and hands seemed to have been removed inexpertly. There were ragged bits of flesh and muscle at the wrist, and I saw a protruding bit of broken spine dangling where Cristoffel’s head used to be.

I hadn’t liked Cristoffel very much. He was poor, and Katrina always said we should be compassionate to those in need, but Cristoffel had been quite the bully, always looking for a chance to take out his pique on someone. He ran in a little gang with Justus Smit and a few other boys who had no personality to speak of.

Cristoffel had tried it out on me once and I’d bloodied his nose for him, which earned me a lecture from Katrina on proper behavior (I was subjected to these endlessly, so I never bothered to listen) and a clap on the shoulder from Brom, which had warmed my heart despite Katrina’s shouting.

I hadn’t like Cristoffel, but he didn’t deserve to die. He didn’t deserve to die in such an awful way. I was glad Sander couldn’t see. He had a delicate stomach and he’d have given us away by getting sick on top of the group below.

There were splashes of blood all around on the track. The men didn’t seem to want to get any closer to the body, though whether this was out of respect or fear I could not tell. They were murmuring softly, too softly for me to make out the words at first. All of the horses pulled on their reins except for Brom’s horse, Donar, a great black stallion three hands taller than all the others. He stood still, the wide flare of his nostrils the only indication that he was troubled.

Finally Brom gave a great sigh and said, loud enough for me to hear, “We’ll have to take him back to his mother.”

“What are we supposed to tell her?” I recognized this voice as Sem Bakker, the town justice. His shoulders were curled forward, as if he were trying to hide from what he was seeing.

I didn’t have much use for Sem Bakker, who was always too hearty when he saw me and thought it was a fine thing to pinch my cheeks and comment on how much I’d grown. He had no children of his own and clearly had no notion of how children like to be treated. I did not like to have my cheeks pinched by anyone, much less the town magistrate with his dirty fingernails.

Brom didn’t have much use for Sem Bakker either, whom he considered as lacking in basic common sense, something that ought to have been a requirement to be a justice. But then most people who lived in the Hollow were farmers or tradesmen, and had no desire to meddle in affairs of the law. Not that there were so many crimes in the Hollow, really—it generally amounted to little more than breaking up fights at the tavern and sending the offending parties home to have their ears burned by their angry wives—though now and then something more serious occurred.

All in all, though, the Hollow was a peaceful place to live, and was lived in by the descendants of the same people who’d founded the village. Strangers rarely visited, and almost never stayed. The Hollow was, in many ways, like a diorama in a box—never changing and eternal.

“We’ll tell his mother what we know,” Brom said, and I recognized the trace of impatience in his voice. “We found him in the woods like this.”

“He’s got no head, Brom,” Sem Bakker said. “How do we explain about the lack of head?”

“The Horseman,” one of the other men said, and I recognized the gruff tones of Abbe de Jong, the butcher.

“Tch, don’t start with the Horseman nonsense,” Brom said. “You know it isn’t real.”

“Something killed that boy and took his head,” Abbe said, pointing at the corpse. “Why couldn’t it be the Horseman?”

“Could be the damned natives,” said another man.

I couldn’t see his face because of his hat, and couldn’t pinpoint his voice, either, though I knew everybody in the Hollow just as they all knew me.

“Don’t start with that nonsense, either,” Brom said, and there was a hard warning in his tone that would have made any man with sense back down. Brom was friends with some of the native people who lived nearby, though no one else in the village dared. Mostly we left them alone and they left us alone, and that seemed to be the best plan for everyone.

“Why not? They lurk around in these woods, taking any animals they want—”

“The animals are wild, Smit, anyone can have them,” Brom said, and now I knew who Brom was arguing with—Diederick Smit, the blacksmith.

“—and we all know they’ve stolen sheep—”

“There’s no proof of that, and since you’re not a sheep farmer, I hardly see what it has to do with you,” Brom said. “I’m the only sheep farmer for miles around.”

“I don’t want to hear your defense of those savages,” Smit said. “The proof is right here, before our eyes. One of them killed this poor boy and took away his head and his hands for one of their pagan rituals.”

“Now you listen here,” Brom said, and I could see him swelling with anger, his shoulders seeming to grow broader, his fists curling. “I won’t have you spreading any of that around the Hollow, you hear me? Those people have done nothing to us and you have no proof.”

“You can’t stop me from speaking,” Smit said, and though his words were brave and his arms were nearly as muscled as Brom’s, I heard a little quaver in his voice. “Just because you’re the biggest landowner in the Hollow doesn’t give you the right to run everyone’s lives.”

“If I hear one word accusing the natives of this murder I’ll know who started the rumor,” Brom said, stepping closer to Smit. “Just remember that.”

Brom towered over the blacksmith, as he towered over every man in the Hollow. He was built on a scale almost inhuman. I saw Smit’s shoulders move, as if he considered a retort and then decided better of it.

“If it’s not the natives that only leaves the Horseman,” De Jong said. “I know you don’t like it, Brom, but it’s true. And you know, too, that as soon as word gets out about the boy’s circumstances, everyone else in the Hollow will think the same.”

“The Horseman,” Brom muttered. “Why will none of you say what’s probably true—that someone from the Hollow did it?”

“One of us?” De Jong said. “People from the Hollow don’t kill children and cut off their heads.”

“It’s a good deal more likely than the mythical Headless Horseman.” Brom didn’t believe in a lot of the things people in the Hollow believed in. It wasn’t the first time I’d heard him refer to someone else’s ideas as nonsense.

Even though everyone in the village attended church on Sunday there was a good deal of what the pastor called “folk beliefs”—and he shared some of those beliefs himself, which was unusual for a man of God, or so Katrina told me. It was something about the Hollow itself that encouraged this, some sense that there was lingering magic in the air, or that the haunts in the far woods reached their hands out for us.

Once, a long time ago, I’d stepped off the track close to the deep part of the forest. I remembered Sander going mad with anxiety, calling for me to come back, but I only wanted to know why nobody in the Hollow went any farther than that point.

I hadn’t seen any witches, or goblins, or the Horseman. But I had heard someone, someone whispering my name, and I’d felt a touch on my shoulder, something cold as the wind that came in autumn. I’d wanted to run then, to sprint terrified back to the farm, but Sander was watching, so I’d quietly turned and stepped back on the track and the cold touch moved away from me. If Brom had known about it he would have been proud of my bravery, I think—that is, if he didn’t box my ears for going where I wasn’t supposed to. Not that he did that very often. Katrina was the one who meted out discipline.

“If you don’t think it’s the Horseman then it’s not someone from the Hollow,” De Jong insisted. “It must have been some outsider.”

“No one’s reported strangers passing through,” Sem Bakker said.

“That doesn’t mean they haven’t passed through, only that no one was aware of them,” Brom said, with that tone he always saved just for Sem—the tone that said he thought the other man was an idiot. “A man could cross these woods and none of us would ever know, unless a hunter happened upon him.”

Sem flushed. He knew what Brom was doing, knew full well that Brom Bones thought he was a fool. He opened his mouth, ready to argue more, but one of the other men cut him off.

“Let’s just return the boy to his mother,” Henrik Janssen said. He was a farmer, like Brom, and his lands bordered ours. Some quality in Henrik Janssen always made me feel uneasy around him. “There isn’t much that can be done right now. If it was the Horseman, then that is part of life here, isn’t it? It’s the risk we take by living so close to the edge of the world.”

There was a general murmur of assent. This would seem callous in other places, other villages, but in Sleepy Hollow strange things were true, and sometimes those strange things reached out their claws. It wasn’t that people didn’t care; it was that they accepted horror in exchange for wonder.

“The boy’s father will be a problem,” Sem Bakker said.

This was a sideways reference to Thijs van den Berg’s habit of drinking until he’d spent all his pay and left nothing for his family. He was the most volatile man in the village when he was in that state, and if he couldn’t find a man to pick a fight with in the tavern, then he’d go home and pick a fight with his wife—a fight she always lost, being small and unable to stand up to his fists.

Every woman in Sleepy Hollow pitied his wife, but they never dared show it to her. A prouder woman than Alida van den Berg didn’t exist in the village. I often heard Katrina and other ladies clucking over what they ought to do to help the family, before deciding that Alida wouldn’t accept their help in any case.

These conversations always left Katrina with sad eyes, and me with an unaccountable need to comfort her—unaccountable because we were at odds over every other thing.

“In the meantime, the family has a right to mourn and bury him,” Janssen said.

There were nods all around the circle from everyone except Brom, who scrubbed his face with his hands, a gesture that meant he was irritated, and doubly irritated on top of it because he wasn’t allowed to express that feeling.

I felt my grasp slipping and gasped before quickly recentering myself, pushing my knees into the branch to keep steady. I was worried that the men might have heard me, but at that moment Brom unbuckled his saddlebag and pulled out a blanket for Cristoffel’s remains. All the men’s attention was focused there, and none of them looked around at me.

Brom knelt beside Cristoffel and carefully rolled the boy’s body onto the blanket before tucking the edges so that none of Cristoffel was actually visible. All that was left of him—that boy who bullied other children and who was so poor that he couldn’t afford shoes—was a sad little lump wrapped in cloth. None of the other men spoke, or moved to help him, and I felt an unreasoning anger at that moment. Whatever Cristoffel’s failings, he’d been a person, and only Brom was bothering to treat him like one. Every other man only thought of Cristoffel as a problem to be solved or explained.

I wondered why most of them had bothered coming along. Then I wondered why the men had rushed out to this spot in the forest to begin with. Someone else must have discovered the body and reported it—but who? I assumed it was one of the men in the party, who would have been on horseback. Why wouldn’t that person have done just as Brom had and wrapped the body up to return to the Hollow? Why had that person left Cristoffel on the trail?

A few moments later Brom mounted his horse, Cristoffel’s body cradled in one arm. The other men followed suit and they slowly filed away, their horses walking at a respectfully slow pace.

Only Diederick Smit lingered, his gaze fixed on the place where Cristoffel’s body had lain. He stood staring so long that it seemed like he’d fallen into a trance. Finally, he turned his horse and followed the others.

My hands were cramped from holding on to the branch for so long and my back was covered in sweat, even though I’d been very still.

“Ben!” Sander said. He spoke in a whisper, as if he were still afraid of being heard by someone. His face was a pale blotch against the fallen leaves.

“I’m coming,” I said, easing backward until I reached the trunk of the tree. Then I carefully swung down, my hands clinging to the branch, and grabbed the trunk with my knees so I could shimmy down. I dusted the bark off my breeches.

“Cristoffel van den Berg was killed by the Horseman!” Sander said, his eyes the size of Katrina’s teacups.

“No, he wasn’t,” I said, trying to summon up the same contempt that Brom had used on the other men. “Didn’t you hear what they were saying? Opa said it was nonsense.”

Sander gave me a doubtful look. “Just because Mynheer Van Brunt says it doesn’t mean it’s true. I mean, everyone in the Hollow knows about the Headless Horseman, and what else could have killed that boy? It’s not as if there are people roaming around taking heads for no particular reason. Only the Horseman does that.”

I would not admit to Sander that what he said made sense. It was the first thought that had occurred to me, too, when I saw Cristoffel’s body without a head. But if Brom said it wasn’t true, then it wasn’t true.

HORSEMAN: A Tale of Sleepy Hollow is published by Berkley Books in the United States

Add HORSEMAN to your Goodreads list here

Grab the U.S. edition from your favorite bookseller or one of these retailers:

Bucket O’Blood Books and Records

U.K. edition is published by Titan Books

Signed hardcover edition available from Forbidden Planet

Signed exclusive edition available from Waterstones

The Mainstreet Trading Company